My daughter’s biggest challenges in the last year have come from learning how to adult. I feel her pain.

Although I am firmly into my 6th decade of living, when it comes to adulting I feel I could be the Imposter Syndrome poster child. I look like a fully-functioning adult. I know all kinds of things about a lot of things–you don’t even want to debate me about the Oxford comma–but I am sometimes shocked by how little I know about the basics of maintaining a life. You really can wing it/kinda fake it for a lot of things. For a really long time. Or, at least, I’ve been able to so far.

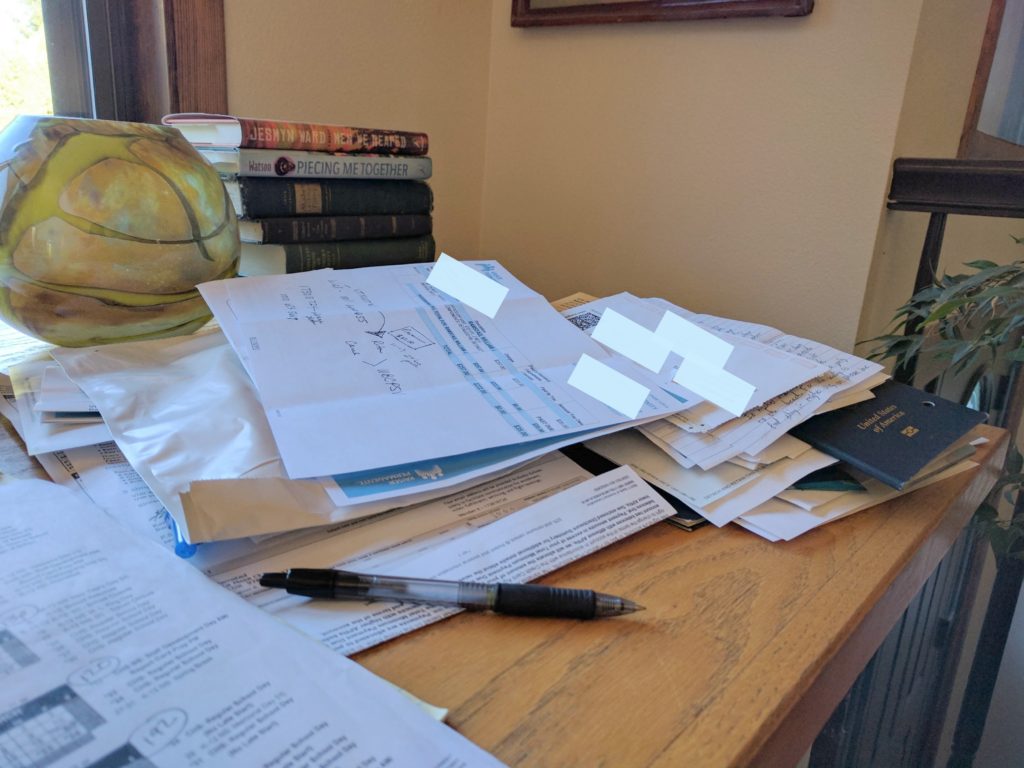

This is not an adulting desk.

But it bothers me that I don’t really know how a lot of things work and feel I have very few practical life skills. If the zombie apocalypse comes or the grid collapses or the bottom of privileged, western life falls out in some other way, I’m toast. I can function pretty well in a world with big box stores and electricity and YouTube and take-out, but I will definitely not be the fittest in any kind of basic survival contest.

I’m not really worried about doomsday scenarios, but I descend from farmers and fishermen and machinists–all self-sufficient people who knew how to grow and make and do with their hands. It bothers me to have so little skill in taking care of my own needs. I’m tired of feeling mildly (or majorly) incompetent a lot of the time, especially when it comes to feeding myself and keeping house. Also, I really like it when I occasionally do something well in these arenas.

I didn’t grow any of this not-organic food, but I made this grown-up meal all by myself.

So the other day I checked this book out of the library:

At first I thought it was going to be another lifestyle porn kind of book–and it does have gorgeous pictures with rustic tile, simple linens, and lots of things in glass jars–but it’s got a lot of substance to it: philosophy, practical strategies, and concrete tools. Most pages look like this one:

There are a few things I particularly enjoy about Erica Strauss’s philosophical approach to food and home. The biggest one? “…don’t be afraid to take it slow at first.”

This is one of the few books I’ve read that makes me think I could actually learn how to do food and home, which makes me want to jump all in. I want to do it all–grow vegetables, can, make my own household cleaners, revamp my household routines–and I want to do it all right now! But this is what my kitchen looks like right now:

And the only way it’s going to look better is if I spend a substantial amount of each day for what’s left of the summer working on it. I’ve also got family to love, and some work to do, and…. I appreciate Strauss’s stance that “this is not an all-or-nothing thing” and that the “ultimate goal of a hands-on homekeeper is to be proactive about shaping your own healthy domestic life.” In other words, she’s not an insufferable purist about the whole thing. In fact, she’s pretty damn funny (as you can see in this post from her blog).

So I’m starting with something simple: making natural household cleaners. I’ve wanted to do this before, but I got stymied by not knowing where to find borax and castile soap in the store. (I kid you not. I still don’t know where to find them, but if I can’t figure it out this time I’m just going to break down and order them from Amazon.)

Baby steps, baby.

Once upon a time I wrote a blog in which our basic premise was that how we do home is how we do life. I still believe that. For three years, life has been an on-hold, up-in-the-air, what-the-actual-fuck, one-transition/calamity-after-another affair. Home has been slap-dash, make-do, get-through-the-day-however-we-can-and-call-it-a-victory sort of thing. Making my own household cleaners might be only the first step on a thousand mile journey, but at least I’m finally moving, and it feels like the right direction. George Eliot wrote that “It’s never too late to be what you might have been.” I generally think that’s a crock of hooey, but when it comes to this I think she’s right.

Now this is a guy with practical life skills.