Doing algebra homework, circa 1978.

I’ve always been pretty sure that I was the last kid they let into the advanced math track. At the end of 7th grade, we took a test to see whether we’d be going into Algebra or some other kind of not-ready-for-algebra math. I don’t know what that was, but my ensuing struggle with math that was more about letters than numbers made it clear to me that I must have been the cut-off kid on the Algebra list, the last one that got into the advanced party.

I have few memories of that math class. I know I had Mr. Elwell, a kind, quiet man with the kind of dark, bushy mustache that lots of men had back in the late 70s. (The kind my second ex-husband, who probably came of facial-hair age at about the same time as Mr. Elwell, still has, although his is now white.) Despite learning very little algebra from him–and learning was generally a huge part of the criteria when determining whether or not I liked a teacher–I liked Mr. Elwell.

I had him not only for Algebra, but also for Driver’s Ed the fall of my sophomore year. That was the year our junior high was transformed into a middle school, and the 9th graders who should’ve been top dog at Sylvester Junior High were instead lowly freshmen when we all migrated to high school together. A handful of teachers came, too, one of whom was Mr. Elwell.

I’m sure one of the things I liked about Mr. Elwell was that it was impossible to rattle him, which made him different from so many of the men I’d known, starting with my dad. Any other teacher probably would have had some misgivings about my driving group the first day we all climbed into the Driver’s Ed car with him. There was Dorrit Norvell, who, I guessed from her skill, confidence, and obvious boredom, might have been driving since about the 3rd grade. She had eyes sharp as her Pat Benatar-esque attitude, and she made it clear that she did not suffer fools gladly. She scared the shit out of me because, when it came to driving, I was everybody’s fool. Unlike most parents, mine did not do one thing to prepare me for Driver’s Ed before it began. No practice drives, no sitting in the car introducing me to the controls, no nothing. I was a driving virgin that first day in the parking lot, and next to Dorrit, with moves as smoothly polished as her nails, it showed. The only saving grace for me was that the third person in our car was Cam Tu Nguyen. She was no fool–but she was a worse driver than me. Our first day Cam Tu tore up the parking lot at about 5 mph, and I thought Dorrit was going to get whiplash from the way her head snapped every time Cam Tu slammed on the brakes, but Mr. Elwell’s calm never faltered.

Eventually we all made it out onto the streets, even Cam Tu. Although I got better at it, driving was not something that came easily or intuitively to me–kind of like algebra, which is maybe why Mr. Elwell was kind to me, the way we are kind to those who are a little slow or a little fragile. Although I was considered to be a smart kid, driving challenged me. The only test I ever failed was the written driving test. I remember coming out of the DMV office and telling my mom I didn’t pass.

“What happened?” she asked.

“Oh, I don’t know…” my voice trailed off. “I think I got confused because of the colors of the cars,” I said.

“What?” She looked puzzled.

“Well, it seemed like the colors of the cars in the drawings had something to do with the colors of the stoplights in the scenario questions. I was sure it did on this one question, and I got the right answer, but then it didn’t on some others…”

“What are you talking about?” she asked, not even attempting to sound sympathetic or like I was making any kind of sense.

“Well, like, if the car approaching the intersection was red, I thought that had something to do with the color of the light, and so if the car was yellow or green…but it didn’t work if the car was blue…” My voice trailed off for a third time. It had made so much sense when I was taking the test. But trying to explain it to my mom, I could hear that it made none.

Later, I would attribute some of my failure on that test to being upset over my break-up the night before with David Ravander, my senior boyfriend who treated me so poorly I finally felt forced to end things between us. That morning of the failed test I couldn’t connect the dots between my broken heart and my foggy, over-thinking brain, but later I saw the lines linking one to the other.

None of my test failure was Mr. Elwell’s fault. He had been a bastion of calm support in that Driver Ed car with Scary Dorrit and Whiplash Cam Tu. Driver Ed cars came equipped with a brake on the passenger side, so that the teacher could, if necessary, save us all in any kind of near-death situation, but I never saw him use it. He didn’t even do it the time I came to a red light, carefully looked both ways to make sure the intersection was clear, and proceeded to turn left.

It wasn’t until after I had completed the maneuver that he said, “Uh, Rita, you might remember that we can’t make free left turns in Washington. You can get a ticket for that.” I felt my bowels begin to turn hot with shame, the way they always did when I’d made a public mistake, but his voice was quiet and calm, and that was all Mr. Elwell ever said about that.

Maybe it was because of that time that I asked him to be my escort for the Homecoming assembly that fall. Or maybe it was because I didn’t really know any of the other male teachers at the high school yet, other than the world history teacher who didn’t like me because I questioned why we spent a whole period watching a Laurel and Hardy movie, or Mr. Carmignani, whose creative writing class I had dropped because he made it clear on the first day that if we didn’t share our inner selves in our writing and our writing out loud with the class, we would not be earning A’s or B’s. I would no more reveal my inner self to my peers than frolic naked down the halls, and a C was unacceptable, so that was that. No creative writing for me.

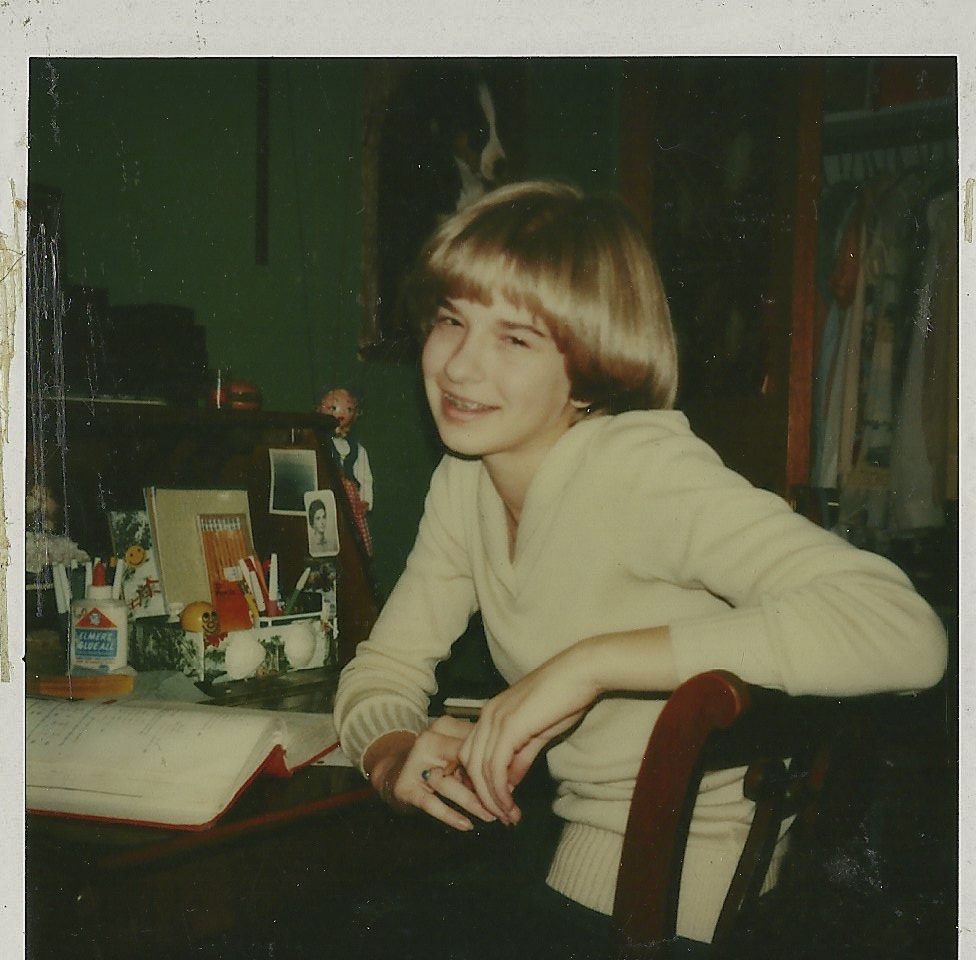

I needed a teacher escort for the assembly because I was the homecoming princess for my class. This was an uncomfortable honor for me. I had no date for the dance and was facing the humiliating prospect of the Pep Club girls arranging to have some boy ask me if no one came forward. I didn’t want to ask my parents for the money to buy a formal dress, because I knew that we didn’t have much of that kind of money, but I was told that I would have to get one. And, I needed a teacher to escort me down the aisle and up the steps to the stage during the big assembly, and I didn’t really know anyone for that, either.

So I asked Mr. Elwell, who seemed both mildly surprised and quietly pleased. At the morning assembly for underclassmen, I hooked my arm into Mr. Elwell’s and we made our way down the auditorium aisle without incident. It was the stairs to the stage that proved to be our downfall. As I stepped up to the first step, I failed to properly lift the hem of my long, formal, faux-pioneer girl Gunne Sax gown, bringing my shoe down on the inside of its skirt. I realized my mistake immediately, but I didn’t know what to do about it, what with my arm hooked into Mr. Elwell’s and everyone watching and me needing to get up those steps. So I just kept going. When I stepped up to the second step, I also stepped further up the hem of my dress. And I did the same with the fourth and fifth and sixth step, even though I knew I was only making things worse. By the time we got to the stage, Mr. Elwell and I were both bent nearly double, as he’d never let go of my arm, and I fell onto it, ears filling with the laughter of my fellow sophomores and those lowly freshmen. Mr. Elwell didn’t say anything; he simply helped me up, re-hooked our arms, and walked me across the stage with as much dignity as he had given me all those times in the driver ed car and in algebra class when I didn’t know the answer.

Years later I would come to see this as a seminal moment, a metaphor for so many things that went wrong in my life. I have had a confounding need to just keep moving doggedly forward, even when it is quite clear that stopping would be the best thing to do–the only thing to do if I did not want my trajectory to end in tragedy. It is has not served me well, nor has my propensity for sticking with others who don’t treat me with the same kind of respect I got from Mr. Elwell.

He was not a very good math teacher for me. I began this essay with the intention of writing about Algebra II, the last math class I ever took because I could no longer fake my way through math without the fundamentals I’d missed in Algebra I with Mr. Elwell. And yet, in retrospect, I can see that he was teaching me something probably more important than how to determine the value of x. He gave me lessons on how to determine the value of I and xy, and although I have been a very slow learner, indeed, now, more than 35 years later, I’ve finally gotten it.

I like to think he’d be both mildly surprised and quietly pleased.

The poor guy I pressured into taking me to the dance.

*******

This piece came out of the last session of my writing class with Kate Carroll De Gutes (the one on writing about serious topics with humor). I almost didn’t attend; I’d had a terrible week, and I was feeling so tired and broken on Thursday night that I didn’t think any good would come of it. But as Leonard Cohen told us, the cracks are where the light comes in. The prompt was simply to write about taking algebra. Although I missed 2 of the 5 sessions, getting this essay out of the class was worth the price of admission. Kate is a teacher in the same gentle vein as Mr. Elwell. (Suck it, Mr. Carmignani.) I highly recommend her classes, which Portland-area folks can take at Attic Institute.