My girl is back, and the house feels right in a way that it hasn’t in months and months and months. I haven’t been locking my bedroom door before going to bed at night, the way I do when I’m the only one sleeping here. Every night when I turn the little knob in the handle, I know I’m being silly. I know that no one is going to break in while I am sleeping. I know that even if someone were to try, that flimsy lock would be scant protection from harm. I feel the absurdity all the more when I consciously choose to leave the door unlocked the first night Grace is home.

Maybe she will need to come in during the night, I think, as if she were still a little girl who might need her mother in the darkest hours of the day.

In these first days back, it is just the two of us here. She is home for break, but both of us are still working. She has papers to write, and I have an all-day training to put on two days after her arrival. Her first night, a Wednesday, is my first day of migraine. I push through pain and fatigue and that constant low-level hum in my skull that keeps me from the sleep I need to conquer the headache. Every Thursday meal is take-out.

Friday afternoon, after the training is done and I am officially released for winter break, she tells me to go to bed. “Only for an hour,” I say. “I need to get my sleep back on track.” Nearly two hours later she wakes me, and we order a pizza. “Tomorrow we are eating real food,” I promise.

The next day I am supposed to attend a work-related meeting, but that night I hardly sleep. I’ve been trying not to take any more meds–I’m already over the recommended dose for the week, and in the past year there have been some stern conversations with me about that in which words such as “heart attack” and “stroke” have been used–but I can’t stand the pain any more. I swallow a pill at 4:00 AM, counting on the odds to be in my favor, so she won’t have to deal with any heart attack or stroke while she’s here alone with me.

Later that morning, after waking again, I’m still in migraine fog, but the pain has lifted. I miss my meeting, knowing that if I go I am guaranteeing myself another night like the one I’ve just had, and I don’t want to play medication roulette again.

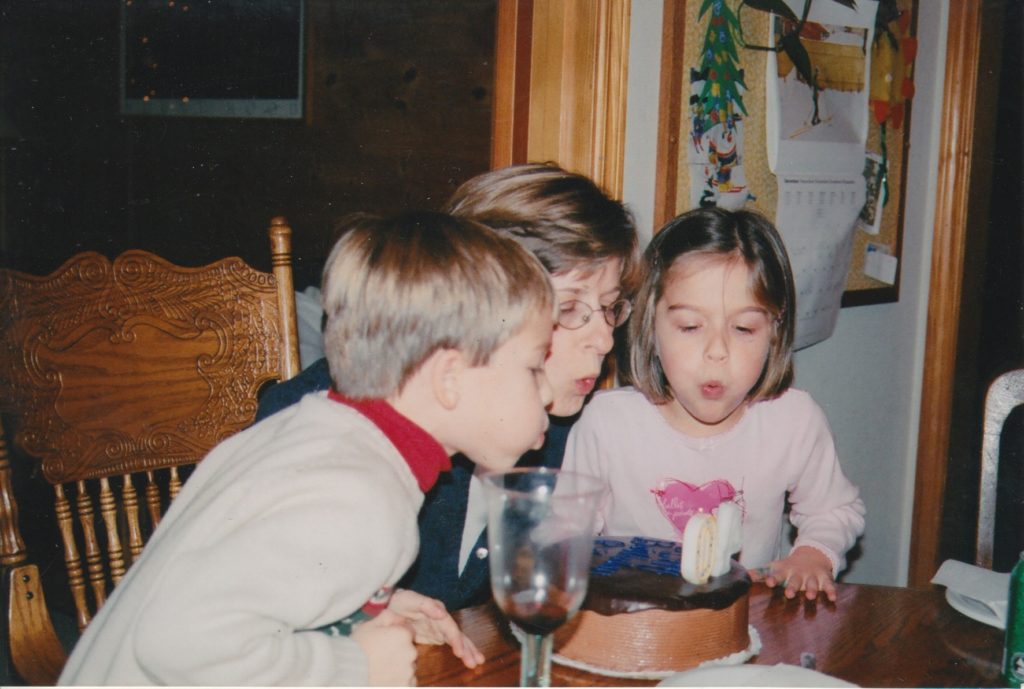

We have a slow day. I putter, picking up the worst of the week’s clutter. We talk. She procrastinates on the paper due by 9:00 pm. I take a shower mid-day and go to the grocery store, so I can make good on my promise to cook real food. I give her feedback on her paper, the way I used to do when she was in high school. She clicks “send” on it, and I make popcorn and we watch a movie, snuggled together with the dogs.

Sunday morning I sleep in–finally–and wake with my head almost clear. Daisy dog and I settle in with a cup of tea and Nina Riggs’s The Bright Hour, a memoir about living while dying of cancer. Riggs and her two sons are so young–she died before turning 40–that I can hardly stand reading it, but I do because the writing is so beautifully sharp, like sunshine on snow.

It is when she writes about wondering how to tell her sons that she is going to die, and I remember mine at the ages hers are in the memoir, that I have to take a break from it. During the year his dad and I were coming apart, Will had trouble sleeping. (Oh, nuts and trees, nuts and trees…) I would let him get out of bed and lie on the couch while I sat at the nearby computer, prepping for my next day’s lessons. When I was finally done working for the day, he’d be asleep. I would pick him up to carry him to bed, his arms gripping my neck as he breathed into it, his long legs dangling from my hips. I knew that in maybe less than a year, I’d no longer be able to carry him that way; he’d be too big and I’d be too small. The idea that there would be nights I couldn’t because we’d be sleeping under different roofs, that I would not be able to carry him because I wouldn’t be there, wrecked me. Reading now, this morning so many years from then, I can hardly stand to imagine all the feelings Riggs didn’t put into her book–or, at least, the feelings I imagine I would have had if, instead of a divorce, I’d been facing a terminal diagnosis.

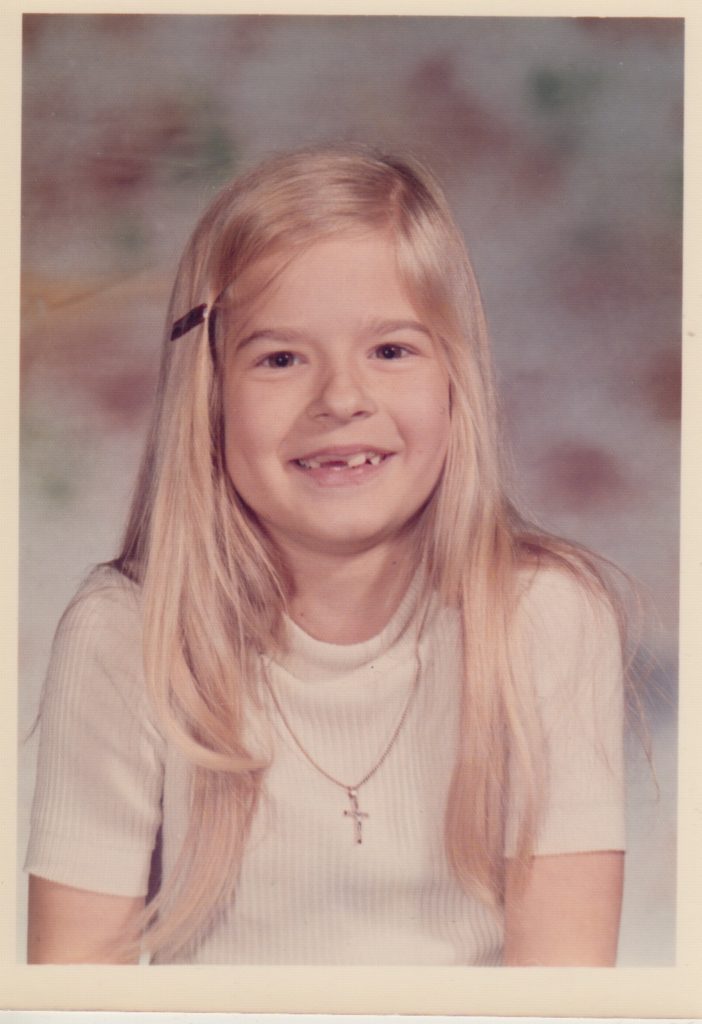

I go to Facebook and distract myself with photos of friends, many from my own childhood. One has a son who just graduated from college. Others are cooking or attending parties or–more so than usual in this most wonderful time of the year–missing parents and grandparents who are forever gone. I see a message from my first best friend; we have both just celebrated birthdays. I reply, reminiscing about the time it snowed during our joint slumber party, and I feel myself choking up.

I miss her so. There are so many people I miss now. In response to my last post here, a cousin wrote, “I sure feel that I have missed much of your life.” Yes. Yes, we have missed much of each others’ lives. I remember the time she lived at our grandparents’ house, an interim stop on her flight from her parents’ nest. When I’d visit, she’d drive me to Baskin Robbins for ice cream and polish my nails, and we’d sleep together in her bed. I remember lying there in the dark, under the eaves of a house none of us can now go home to, listening to her tell me stories about her mother and her sisters and her fiance, who was living in another state for reasons I don’t remember, and I miss her and our grandmother and that house.

I think about the horribly corny movie Grace and I watched on Friday (The Christmas Prince), which we howled through because it was so full of terrible cliches. When the main character tells a child that her dead parent is always with her and never really gone, I think: That’s such bullshit. Why do we tell each other these things that aren’t true?

I cuddle the dog, sip the tea, wondering when Grace will get up. I think about how I so often feel when I am alone in the house, contemplating what I assume will be my future, and how it feels so different now, just knowing that she is sleeping in the room beneath me and will soon come up the stairs, groggy from sleep.

I think about how I missed half the nights of the second half of my son’s childhood. About how I have missed years of the lives of people I love. About how I am entering the third year of missing half of Cane’s days, and he mine. It is not enough to send cards or exchange Facebook messages or see each other once every few years. We need to share meals and errands and hugs. We need to carry each other to bed, whisper truths in our shared dark.

Unlike Nina Riggs, I am still alive, and I find myself wondering what I would want, how I would live if, like her, I learned on the night of winter solstice that my condition was eminently terminal–that I could not count on years in which to figure out what is essential and what can be–should be–let go.

I wonder why it is only in the not-something that I see so clearly what a something is. That it is only in my girl’s absence that I have seen all the things most precious in the life we once shared, and that it is only in her presence again that I am seeing the true outlines of all that my solitude does and does not hold.