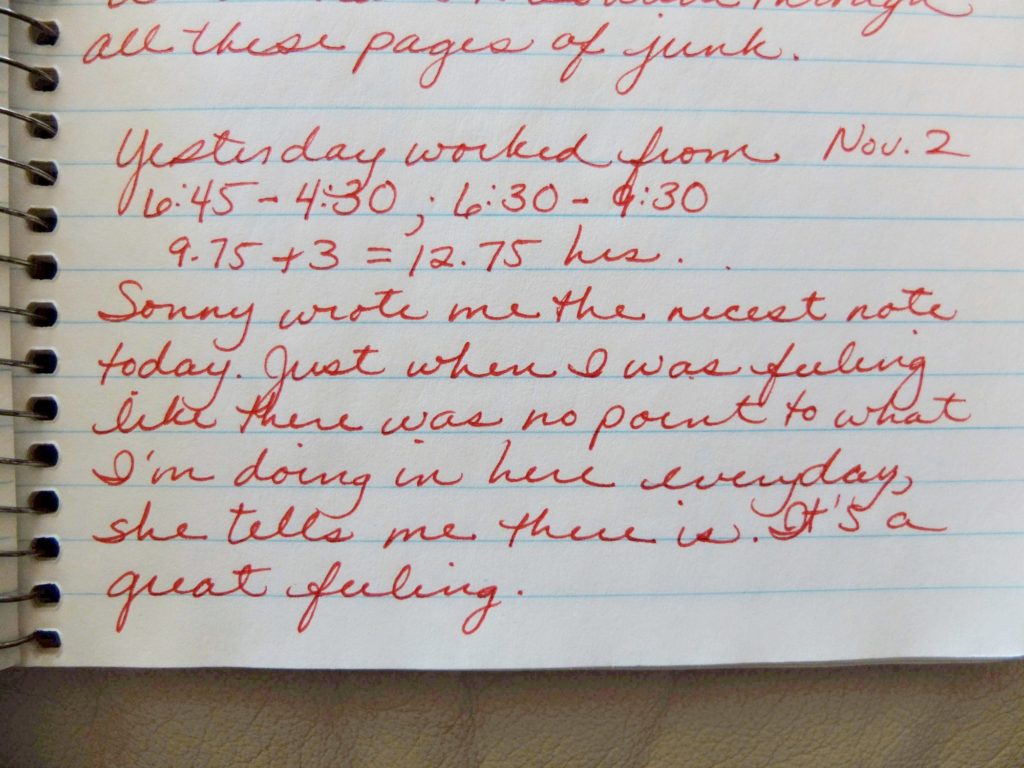

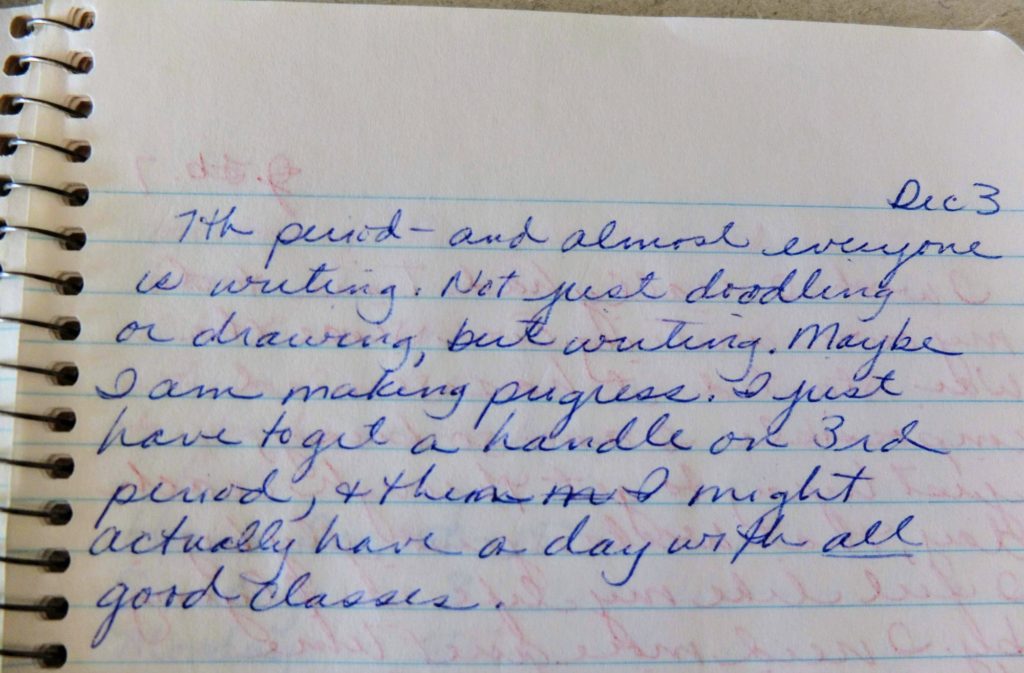

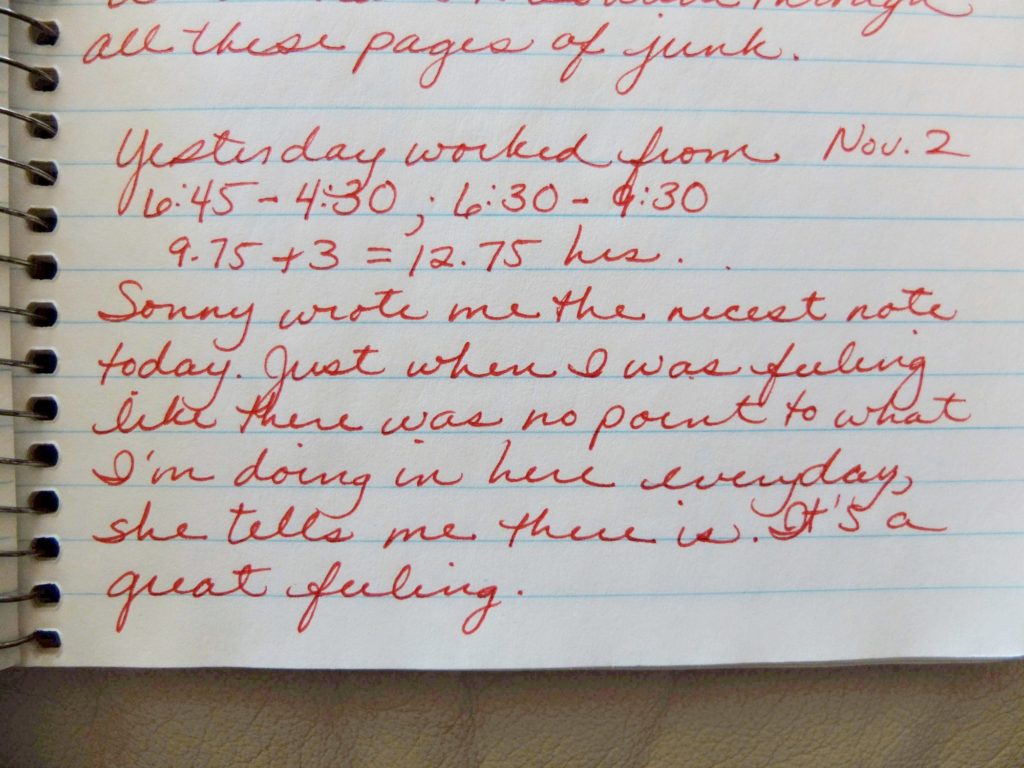

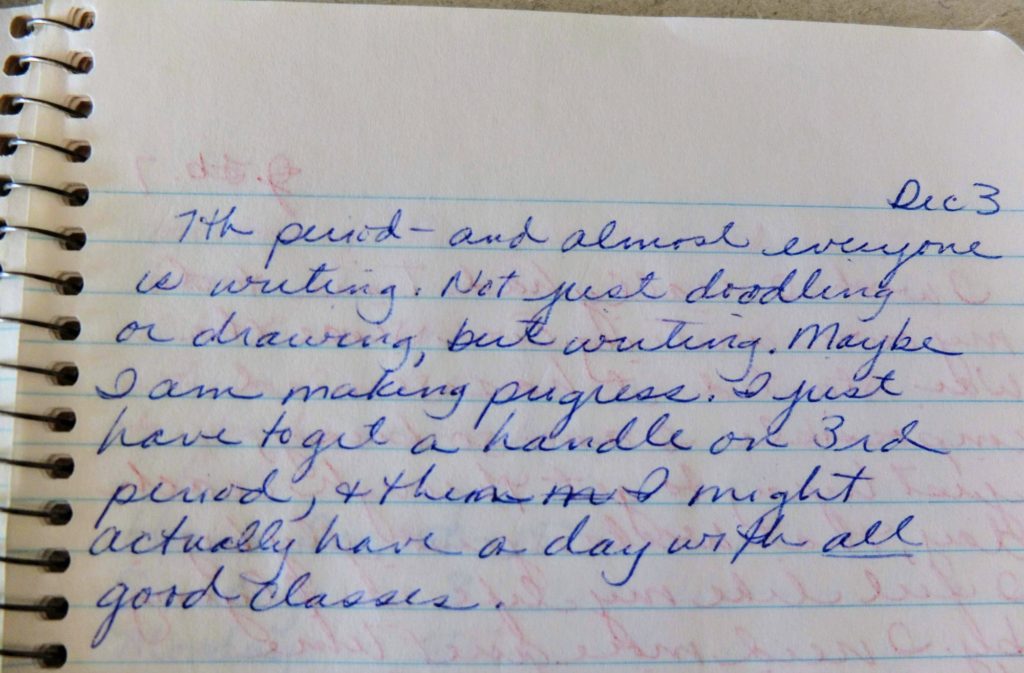

I found your journal in a box in the garage this summer. Not your real journal, your “fake journal,” the one you wrote in at the beginning of every class so that you could model journal writing for your students. I love that you dutifully modeled all year long even though you felt it fake and doubted its value–because how else would I be able to revisit you now, 28 years later, and be able to see so clearly who you were?

In just that one short entry, I see all of you, First-Year Teacher Me: your candor, your questions, your limitations, your doubts, your pragmatism in the face of those questions and limitations and doubts. While your journal has more than one outrageous statement that I know you didn’t really mean (“freshmen should be shut up in cages until they are juniors”), I see how much you wanted to do right by your students.

I love not just your journal entries, but also your lesson plans and lists of things to do, even as they make me kinda want to cry, seeing how seriously you took it all. Could anyone have ever been so earnest about planning for freshman cheer practices? (Yes, you could. You were. God help you. Call on socks!)

As I read these pages full of to-do lists and time logs and lesson plans and journal entries, with their stories of botched lessons, no curriculum, departmental warfare, unclear purposes, cynical colleagues, and endless meetings, I want so badly to reach back in time and give you such a hard hug. I want to tell you that, yeah, you were doing a lot of things wrong, but you were also doing a lot of things right. I want to sit you down and assure you that, no, you’re not a weak whiner–that year was hard, real hard, harder than it should have been.

Oh my god, First-Year Teacher Me, just the log you kept of your hours! (Remember how an administrator suggested you do that? So you could see where you were “wasting time”?!) No wonder you were so exhausted and cranky. No wonder that fragile baby marriage of yours didn’t survive it.

It was so strange and unsettling, to read the words of this person (you!) who is both me and not-me, and to see you laboring so hard to author the beginning of a story whose plot line is now irrevocably written. There’s no revising it now, much as I might like to. There are only the next chapters, which are in some ways as much a mystery to me now as yours were to you then.

You see, I found you during a summer in which I was surprised, again, to find myself in a place I don’t want to be. It was a summer of unpacking. Unpacking boxes. Unpacking relationships. Unpacking a home, a career, a family, a life. Back in early August, not long after I found you, I was reading Dani Shapiro’s Hourglass, in which she quotes Jung–

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life, and you will call it fate.”

–and those words pushed me, who has so often felt my life directed by things outside my control, to unpack yours. As I read and re-read them, part of me felt for you the tenderness I always feel for the young and floundering, but another part of me felt so frustrated and impatient (and if I let myself go there, close to despairing) as I listened to you, First-Year Teacher Me–because in too many ways you could also be Fifth-Year Teacher Me or Fifteenth-Year Teacher Me or Last-May Teacher Me.

As I looked back at you through the tunnel of your journal, I could hardly believe how many of the questions and struggles you wrestled with then would follow you through your whole career. Are, in fact, still with you today, 28 years later. I don’t know if you could have stood knowing that when you were 25.

I can hardly stand knowing it now–and seeing that you already had so many of the answers (or at least the beginnings of them) then. You just didn’t know you had them. You just didn’t listen to yourself. What I can see so clearly from here–what your words have made conscious for me–is that you were in a toxic situation that you endured by taking whatever positive crumbs you could find and letting them be antidote enough to keep you alive in it.

And that is how you are going to get through the next 27 years. First Year, you are going to change schools, jobs, husbands, and homes in search of peace, but it is going to elude you. You’ll spend some years frantically cultivating other opportunities, but you’ll never take them. You won’t know why, not really. You’ll wonder if it’s because you are too cautious or too weak or too scared, and some years those wonderings will tear you up, but near the end, when you finally realize that it’s too late to come up with a different answer to the question of what you are going to be when you grow up, when you find this journal in a garage in the middle of a difficult summer, you’ll understand that you stayed more because of love than fear.

Love is always the reason you stick with hard things. Some part of you, deep down, loves the people you serve and work with, and you aren’t going to walk away from them. Some part of you, even deeper down, loves and can’t give up on the wildly beautiful noble idea of public education and its promise that through it anyone can become anything. Nor can you give up your belief that words can save lives, and that what the world needs most is not your words, but more people who can read everyone’s words and write their own.

I am not a fan of martyrdom, so I’m not going to tell you that you that staying was the right thing because you did it for love, which conquers all. It doesn’t, nor should it require self-sacrifice. But neither am I telling you that you should have walked away. Walking away from love should be a move of last resort.

What I can see so clearly, so consciously now, is that even in your first year the problem was never lack of belief or discipline or caring or even skill, much as you doubted all of those things. They are all your greatest strengths, but what you didn’t know then is that our greatest strengths and greatest weaknesses are always two sides of the same coin. Your dedication to people and ideals and your determination to use your gifts in serving them is both the source of your power and the thing that will zap it. It is the push that makes you long to leave the work and the pull that holds you to it. It’s what fuels both your best moments and your worst.

When we love it is sometimes so hard to know where lines are or need to be: between want and need, between supporting and enabling, between our allies and our enemies, between others and ourselves, between right and wrong. I see you crossing back and forth over all of those lines, again and again and again, and I can see that perhaps you didn’t need to leave the path; perhaps you just needed to walk it differently.

I hesitate to even write these words to you, First Year, because they can so quickly be used to keep us from seeing and addressing larger societal and systemic issues that make this work so hard for everyone I know who does it. But what you need to do–what we all need to do, if it can be done–is to figure out what you sensed then: Learn how and when and why to say “no,” so that you will be better able to say “yes” to the things that will allow you to love better. And the first thing you have to say “yes” to is yourself: A dead martyr can’t serve anyone.

Some say that when the student is ready, the teacher will appear. I don’t know about that, but I do know that things sometimes work in ways we’d never expect. Who would have ever thought that it would be you, faltering First-Year Teacher Me, with your fake journal scribbled together in brief moments at the beginning of your classes and the middle of cheer practices and the last moments of your too-long days, that would impart such important lessons to Nearing-End-of-Career Me? Certainly neither of us, but I’m glad that you wrote these words down that appeared, somehow, from a box I hadn’t looked in for years. Thanks, Teach.