Over the past few weeks I subbed a few days in a high school entrepreneurship class. It was the easiest sub gig ever, as there was a teacher teaching the class. She is a business owner with all kinds of qualifications to teach the subject, but no teaching license. I was there to meet legal requirements to have a certified teacher in the room. Because I wasn’t teaching much, I was often able to sit back and participate as a co-learner with the students.

That is how I came to be listening to Brené Brown talking about shame and courage and risk and getting “in the arena” in a new way. It’s how I found myself thinking about her ideas within the context of work and money and worth in ways that aren’t typical for me.

Let me back up a little.

When I officially “retired,” I did so with dreams about living a simple life. I just wanted a small, quiet, uncomplicated existence in which I could be healthy and be present with and for the people I love. My labor would be focused on making our home and caring for our family and friends, and that would be purpose enough for me. I was sure I could be content with much less money than I had become used to having because I would need less in our simpler life.

For the most part, this dream has come true.

For the most part.

There have been some points of minor rub. While it has been wonderful to finally have the time to do life’s labors in ways I’ve always wanted to do them–We’ve been eating well! I love eating well!–it hasn’t been quite as satisfying as I hoped it might be. Homemaking chores are often more boring than creative (there: I said it), and the Sisyphean nature of much of them has, at times, prompted moments of existential malaise. My new work has also given rise to questions about and shifts within my identity. This, in turn, has created shifts in my relationship with Cane that he claims not to feel but that sometimes feel tectonic in nature to me.

And then there’s money. (Isn’t there always money?)

I’m not substitute teaching because I’m bored or because I miss being in schools. I’m subbing because I need/want to bring in more money than my pension provides. We do live pretty simply and happily simply, but in the past year things have happened that I didn’t anticipate. Things that required money.

(Why didn’t I anticipate them? I don’t know. Things always happen. Things that require money. I do know this.)

Right now, subbing is the gig that gives me the biggest financial bang for the buck of my time (which is, of course, my life). It’s pleasant in many ways, and (because the world of public education is so often nonsensical) it pays more per hour than the more creative and challenging professional development work I’m also continuing to do. It doesn’t take much out of me, making that simpler life more attainable than it would be if I engaged in other forms of work. But.

It is nonetheless messing with the whole simple-life thing. Just adding a day or two of work outside the home each week is tipping some balance I was mostly achieving about making home my work. Even though subbing is far less taxing than the work I used to do as an educator, I still come home from it worn out. I come home from it not wanting to make dinner (or run a load of laundry or do dishes). I come home from it less able to be present with my husband or daughter or friends. It also puts pressure on the days I am not doing it, as I scramble to play catch-up.

And. It meets few needs/wants other than the one I have to make money. It feels a lot like babysitting, a work gig I purposely never did much of as a teenager. Babysitting is great for some, and it fills important needs, too–but it’s never been great for me. If there are better alternatives, I don’t like the idea of spending any of what’s left of my life doing something that’s not really for me, for the sole purpose of earning money. If I have to engage in money-earning, I guess I’d like to get more than just money from it.

(Here is where I feel compelled to acknowledge my good fortune that that makes all of these questions/wonderings possible. I know I’m lucky that these are the questions I get to contemplate.)

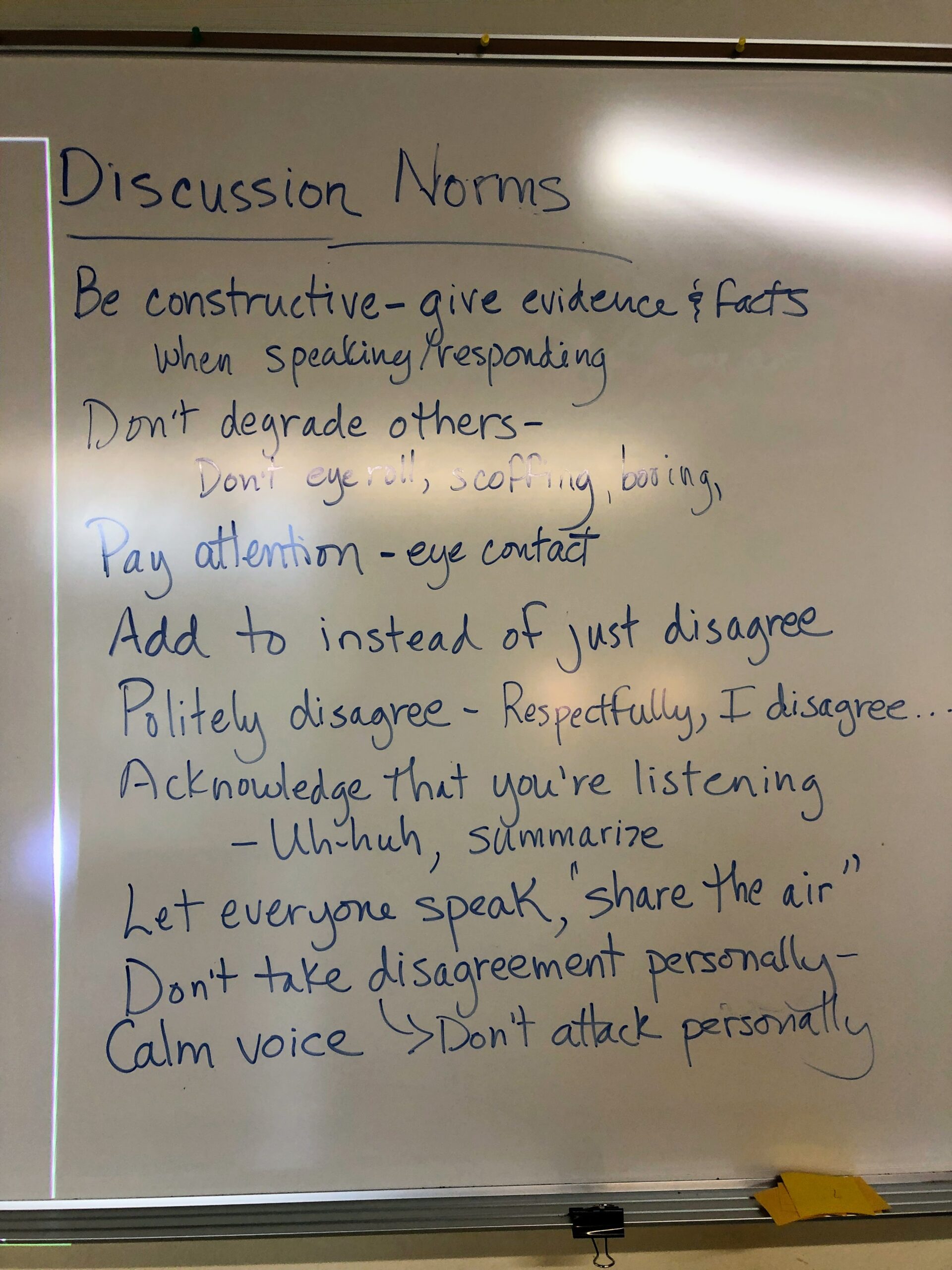

So, that’s the mental/emotional/physical landscape I was traveling through, babysitting in a classroom and stewing a bit in these questions about my current situation, when Brené began talking to all of us about being in the arena. As I listened, I began wondering what “the arena” even is. When I was a full-time educator, I know that I was for-sure in one. I was taking risks, I was working for change, I was often–to use Brown’s language–daring greatly. That meant I was also, more often than I liked, falling down in the dirt and failing–because, according to Brown, that’s an inevitable part of being in the arena. So, education was clearly an arena.

But am I in one now? Most people would think that retiring is about exiting arenas, but maybe my decision to transform myself into a full-time homemaker was about getting into a different arena. Maybe the friction I’m feeling is evidence that it is, in fact, a kind of arena. Or maybe I’m not in any arenas at all and I just jumped into a risky situation in a kind of half-cocked way that was more foolish than courageous. I am not sure where I am vis-à-vis Brown’s arenas, but I know that wherever I am is not a place I’m entirely comfortable being.

All of this listening/thinking/wondering in combination with hours of not a lot to actively do took me back to Substack. Sitting in those entrepreneurship classes while perusing newsletter after newsletter (a term that doesn’t entirely make sense to me, because the ones I read are more like blogs or magazines) turned a big lightbulb on in my head: Substack writers that use paywalls are entrepreneurs. Instead of being hired as writers, they are putting out their own shingle. They are selling their work directly to consumers. They are building businesses.

This realization (which, really, should have been kind of a duh! moment) brought up so many feelings! Of ick and shame and fear and other emotions that Brené talks about! (And, also, a little bit of excitement and possibility.)

(See how I even have to put those other emotions as an afterthought, and in parentheses, and qualify them as “little”? Almost as if I don’t want those bigger, upfront emotions to notice them. As if I don’t want you, my dear-to-me readers, to notice them.)

This realization + my feelings + Brown’s thoughts about arenas lit up a whole lot of other ideas/wonderings–about art, craft, labor, money, cultural mythologies, gendered roles, my history with writing and publishing, and more. Thanks to the serendipity that put me in that class at this point in time, I’m thinking about these things through different lenses than I’ve previously done. As I’ve done so, a kind of lethargy that’s plagued me for a very long time is beginning to recede. I feel my pulse quickening in a way I’d almost forgotten it could do. A way I feared I was perhaps too old to feel again, despite all the voices in the world telling me that I’m not.

And that feels good, even if not entirely comfortable. It feels good to be more curious than avoidant, and more open than closed. (Hmmm…maybe I’m getting more out of the sub gig than I thought?…)

I have no grand conclusions today. Just questions and beginnings of questions. I’d love to hear what you think about any of these things I’ve touched on here. I know we all have to figure out our ways of working and being in the world, and it’s great to learn from others’ experiences.

Other tidbits from the week…

Has anyone ever played this?

We’re looking for a good game for Christmas day for 4-5 adults who don’t want to have to learn something big and complicated. Suggestions very welcome.

The splint has been replaced by a cast, which is supposed to be on for 6 weeks. Typing is a much more reasonable undertaking now. Not loving it, but it could be so much worse.

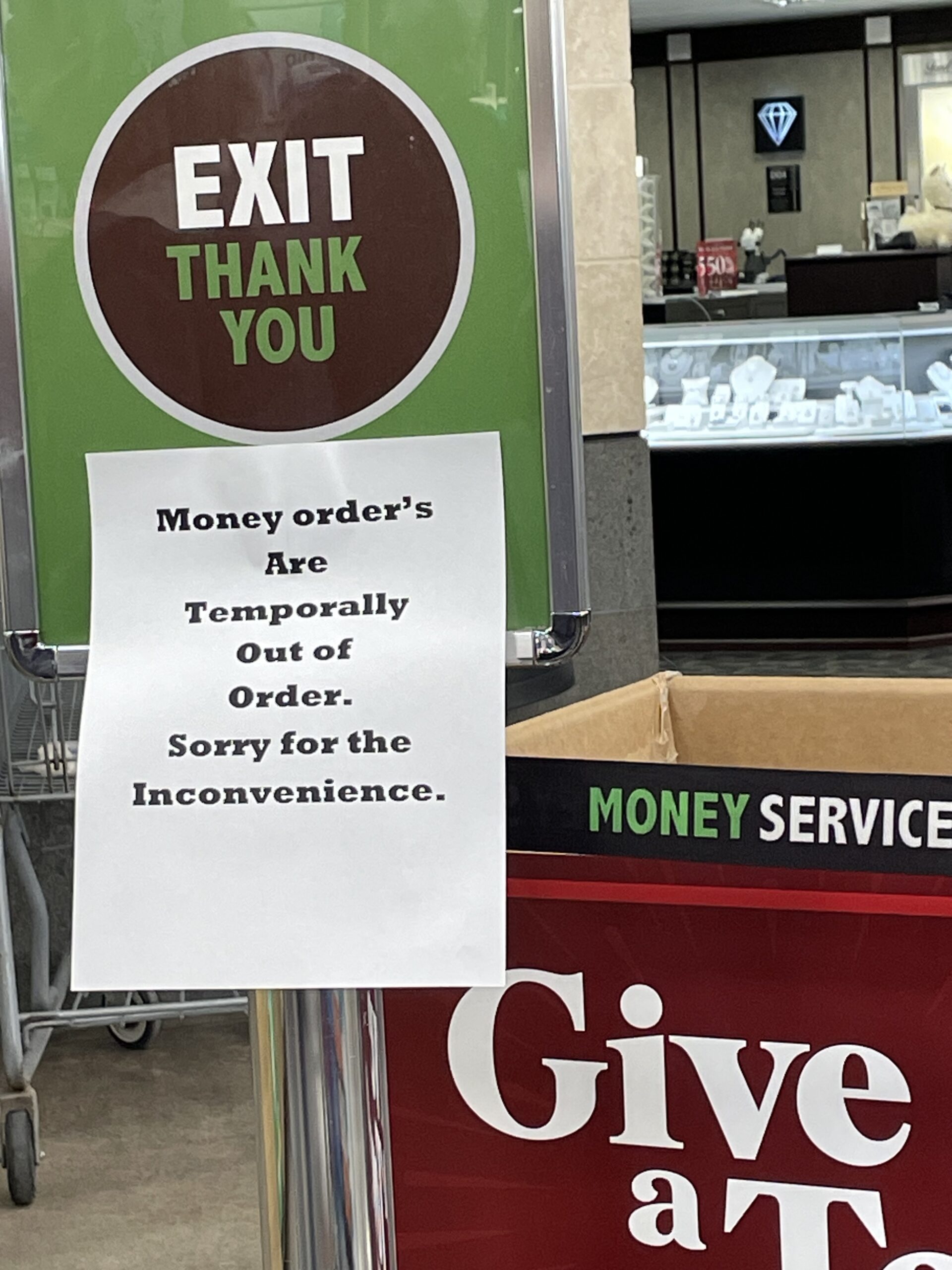

On the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, while waiting in line to make a return at a crowded Fred Meyer (Kroger), seeing this felt like the universe was giving us all a gift of some found poetry .