I thought I had spurned productivity culture. I thought I had embraced simplicity and small-life living. I thought I had divorced worthiness from accomplishment. I was wrong.

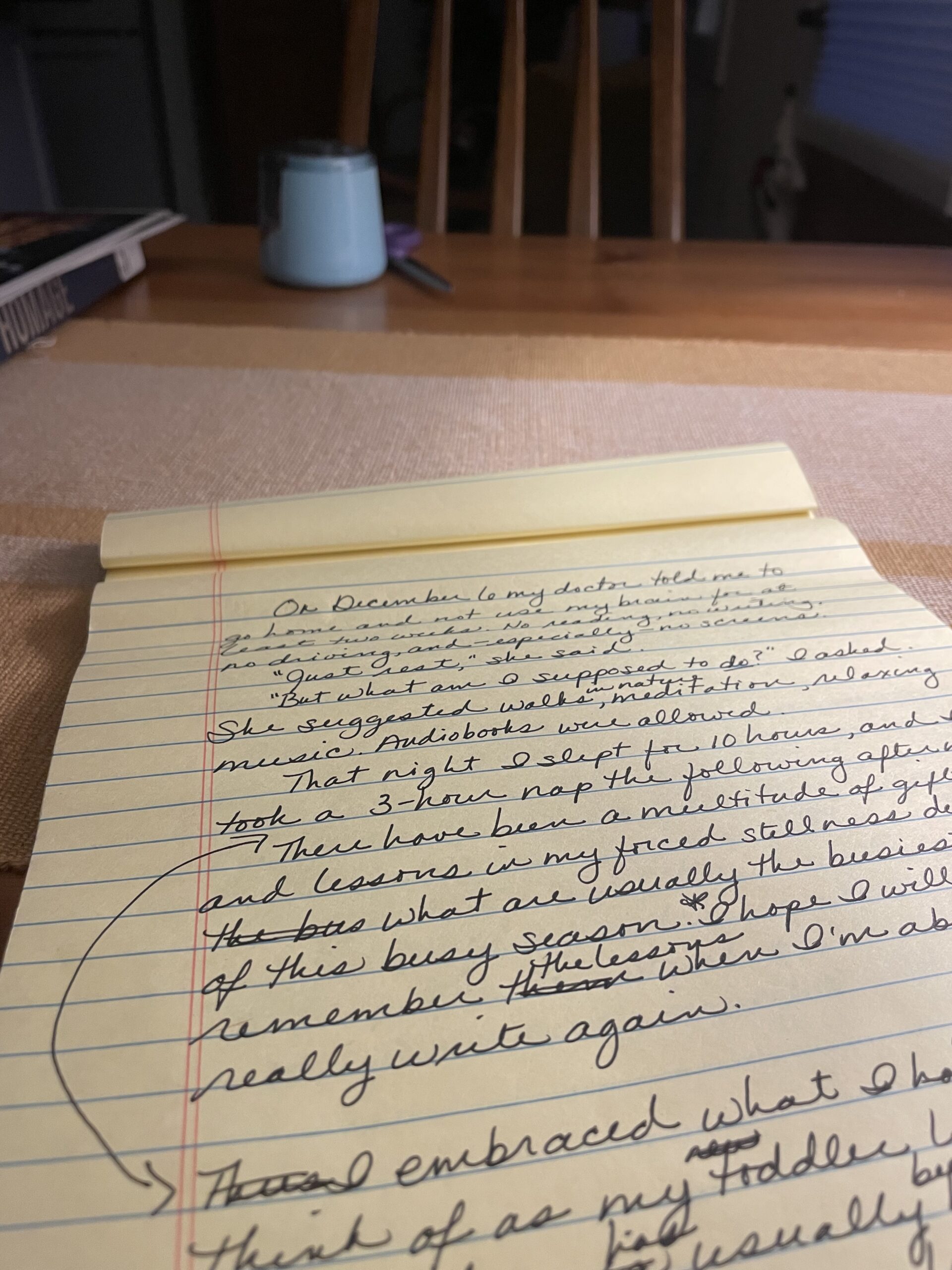

When, 19 days before Christmas, in the wake of a concussion that wasn’t healing, my doctor banned me from screens and driving and reading and even freaking jigsaw puzzles, prescribing near-total rest for two weeks, my first thought was: How am I going to get everything done? This was quickly followed by: What am I going to do all day?

After returning home from that appointment, I stretched out on the couch in our front room. Waning winter sunlight filled the space. I took a few deep breaths.

In-2-3-4, out-2-3-4.

Each time I expelled air from my body, as I felt my diaphragm sink into my spine, I released another thing from my to-do list. Our tree was in a stand in the corner of the room, but it was bare. Presents were not selected or purchased, much less wrapped and put in the mail. Dinner wasn’t made, the bathroom wasn’t cleaned, and the laundry wasn’t put away.

So be it (2-3-4).

While I’d felt some panic with the doctor, what I was beginning to feel was an emotion that surprised me: relief. I had permission to not do all the things. Doctor’s orders.

Only then did I begin to feel and understand how much difficulty I’d been having since my fall 3 weeks earlier. Despite breaking my wrist and seriously hitting my head, I went to work the day afterward. I’d been plowing through all my tasks and obligations ever since, as if my cast and recurring headaches were just minor inconveniences to be tolerated and navigated.

The next day, I ordered a coloring book and a set of nice markers. (Coloring was allowed.) I broke my screen fast just long enough to check out several audiobooks from the library. I finally broke down and switched my Spotify account to Premium, so I could listen to music without interruption from ads.

My days took on a new rhythm. After seeing Cane off in the morning, I’d sit at the table with a cup of tea and color while listening to music or a book. I’d then take care of some kind of household task–light cooking or cleaning or decorating for the holidays–and then I’d need to sit or lie down for a bit. (That might turn into a mini-nap.) Lunchtime followed that, which was followed by a real nap. Late afternoon would bring more coloring or some other activity involving pencils, paper, paint, or thread, usually with a snack and more tea. Then Cane would be home.

“I’m living like a toddler,” I told him after a few days. “Meals are events, I need naps every day, I play with toys, I have easy chores, and I rarely wear shoes.” I took to wearing a garment that is really nothing more than a soft, voluminous onesie (but without crotch snaps, which might have made it perfect).

When I wasn’t bumping into difficult thoughts about aging, mortality, and what constitutes a self, or chafing against my frustrated desires to read and write, the time was, in its own, weird way, kind of wonderful. Instead of spending our evenings zoned out in front of the TV, Cane and I began spending our evenings being together in a way that felt more present. We’d turn on music and he’d read, and I’d stretch out on the couch and just…be. I’d think about things while looking at a blank wall and listening to the music and…rest. He began painting again, something he hasn’t done for years, and I loved watching him paint while I did…nothing.

Although it was exhausting to be exhausted all the time, and I missed being able to drive and go out and see people as I was used to doing, and it was truly frightening to lose my ability to do so much of what makes me what I think of as me, there were aspects of this new way of being that were deeply satisfying. Just being able to sleep! I was sleeping long and deeply, for the first time in, maybe, decades. I was resting when I felt tired. Doing crafty things without feeling like I really should be doing something else–something more useful, or potentially useful. Something I am better at doing.

At some point, I realized that, if I chose to, I could live the toddler lifestyle even after my brain healed. I realized that, for the most part, I could have been living it all fall. I am (mostly) retired! I have been for more than two years! I retired early so that I could rid my life of toxic stress! And then I realized how sad it was that–despite all I thought I had done and changed to live in a healthier way and re-program myself from harmful cultural ideals regarding the relationship between work, productivity, and value–it took a freaking broken bone and brain injury for me to finally give myself permission to truly simplify my life. To truly care for myself.

It took that for me to see how tired and stressed I’ve still been, and how much I have not given myself permission to simply exist, despite my intellectual understanding of all the -isms at play in thinking that I need to be useful to justify my existence (namely, capitalism, sexism, and ableism). It goes without saying (but, if you’re like me, maybe I need to say it) that I am not talking about shirking things that must be done and singing la-la-la while things fall down around you. I am not writing without awareness that sometimes, often, we cannot care for ourselves as we truly need to be cared for because of broken systems and other limitations we live within. I know that some of you are living through nearly untenable situations right now, the kind that break and remake you, and people you love are absolutely counting on you to be there for them. And you have been and will be, just as I have when needed in those ways.

I am talking about how we live when our lives are what we think of as normal, when we are not responding to active crises. I’m talking about what we do when we have pockets of time (even very small ones) that we can choose to fill with rest or quiet or joy, and why we so often fill them with numbing agents (looking at you, social media) or tasks that may not need to be done. What I am saying is, even though I was living as a toddler, the things that really needed to be done did get done, and the ones that didn’t get done didn’t matter.

One morning in the dreamy space of days between Christmas and the new year, I found myself lingering at the breakfast table with my daughter and her husband. He was with us for only two short weeks before he had to return to the country he lives in, a continent and ocean away. Our time together is scarce, precious. We were sitting and talking, about nothing and everything, and I had the thought: Oh, I should probably get up and do something.

Then I thought: Why?

Then I thought: We are doing something. We are forming bonds, we are enjoying each other’s company, we are replenishing ourselves, we are making memories. We are being together. And I settled into where we were, grateful for the realizations my time of rest have given me, glad I didn’t get up and start bustling around the kitchen. It got cleaned, eventually, when our conversation reached a natural ending.

I want to think that I am going to be able to hold onto the silver lining of this experience forever, but I know its lessons will probably slip away from me. These seem to be truths I need to learn over and over again. So what I am saying to you here is as much for myself as it is for anyone else. And this is what it is:

Try pretending that something has happened to incapacitate you, and see what you really need to do and what you might let fall away. Then let it fall. Don’t wait for the broken bone, the brain injury, the catastrophic accident, the terminal diagnosis. Give yourself permission to take a nap, color a picture, bake cookies, make art (even bad art—maybe especially bad art), spend a whole morning–a whole day–eating and talking with someone you love. Do it because life is precious, and you–like a wildflower or a songbird or a even a worm–deserve joy and rest just for being alive. Do it because our work is long but our years are short, and one day you won’t be able to do those things.

Do it just because you can.

A technical note: Rita’s Notebook is moving to Substack, with a new name and slightly more focus. You can find it (and this post) here. I’d really appreciate it if comments/conversation about the post can happen there.

I’ll publish in both places for a bit, but I’ve made the decision to abandon the WordPress ship. This site has long had tech issues that need fixing, but I have neither the skills to fix them nor the desire to acquire them. If you’ve been reading here, I do hope you’ll follow me there and subscribe. (One of my tech issues is that I no longer know who my subscribers are or even how many people click on a post.) Although many Substack publications require paid subscriptions for full access, mine will not. I’m happy to answer any questions anyone has about the decision to change platforms.