Hi, I’m Rita, and I’m a librarioholic.

The past few months I’ve been checking out piles of library books that languish on my nightstand past their due dates only to be joined by more books before I’ve returned them, and I’m starting to think that I love something about the idea of books more than I love actually reading them. I fantasize about spending a whole Saturday curled up on the couch with a book, but I never turn that fantasy into reality. Perhaps what I love even more than reading a book is the search for it, the anticipation of it, the possibility within it, the comfort of it. Some thing a book represents, more than the thing it is.

I blame this book habit–and my impressive fine history–on my childhood. Which means, of course, on my mother, the one who introduced me to books and libraries.

She has told me that she began taking me to libraries before I can even remember. She dropped me off for a weekly “creative drama” class when I was just a toddler. “I always wondered what they had you do there,” she’s said. She doesn’t know, having raised children before the advent of helicopter parenting and outsized fears about child safety.

I have no idea what we did, but I’m guessing I liked it. I’m guessing I felt safe and happy, the way I’ve always felt in a library.

Later, when I was trapped in the bog of misery that was my 6th grade year, she’d take me there every Saturday. I’d drop off the stack I’d checked out the previous week and leave with a new one, each volume a friend to get me through the long weekend ahead–because those weekends in which I needed distance from my parents but lacked proximity to my peers were so, so long.

Back then, I did lose whole days to the pages of books. I wasn’t discriminating because you don’t have to be when time feels unlimited. I read trash. I read weird things. I read things I’d read 20 times already. I read some classics, too. Compared to now, there was very little like YA then, and I struggled with being both too old for the children’s section and too young for the adult section. The closest things to books that felt written for someone my age were some corny series from the ’50s (Beany Malone was my favorite) and Beverly Cleary’s really dippy Fifteen and Jean and Johnny. (These did not equip me well for the late 70s teen social scene I was entering.) I did eventually discover the entire Judy Blume oeuvre and Dinky Hocker Shoots Smack, the title of which alarmed my father enough that he initiated a Serious Talk, a conversation I did not enjoy, and, of course, Go Ask Alice, which kept me away from drugs for a very long time because Alice was a pretty sweet, innocent kid (like me) and look what happened to her when she used drugs just once, and she didn’t even mean to! And it was a true story! (Except, it wasn’t. But we didn’t know that then. And by “we,” I might mean only myself and the writer I just linked to, possibly the two most naive teenagers of our era. I bet she read 1950s YA, too.)

All of which is to say that, for me, books were entertainment and companionship and guides for living, and the portal to them was the library. The nearest bookstore was a B. Dalton’s all the way out at the mall, and I didn’t have anything like enough money to buy all the books I needed even if they’d had a large stock of them, which they didn’t. My habit only deepened when I got my first job, which was (of course) at our local public library, where my favorite task was sorting the books for shelving. That’s how I discovered all kinds of books I’d never previously encountered, including a guide to teen-age sexuality that I snuck out of the building and never returned, and which was the source of my mortification when, as a college student, I realized that my mother must certainly have found it when she cleaned out the closet in which I’d hidden it.

I’m such a library addict that I purposely hooked my kids on it, too. When they were preschoolers I’d take them to the library, and right after that we’d go to McDonald’s, where they would play in the Lord of the Flies-esque play area and I would eat french fries and read a few pages in peace (or what passed for peace in those years). It was a total win-win. I knew exactly what I was doing, and I did it on purpose. I wanted them to love the library like I did, and I knew that associating it with McDonald’s–because we almost never went there at any other time–was a sure-fire way to get them hooked create that love.

(Remember, it’s all my mother’s fault. She started it.)

Now, I find myself in a season of life with much more opportunity to read, but I’m still not the kind of reader I was in 6th grade. While I’m no longer responsible for the feeding and physical survival of young humans, I do still have a life of my own I need to keep going in a reasonably healthy manner, and there are no such things as whole days spent on the couch with a book. When I do let myself indulge in a couch/book treat, I pretty much always fall asleep after just a few pages. Most of my reading is done in snippets–before bed, in the bathroom, while I’m waiting for water to boil or sauces to simmer, when I’m eating. Sadly, there are far, far more books that I want to read than can be read in the snippets available to me.

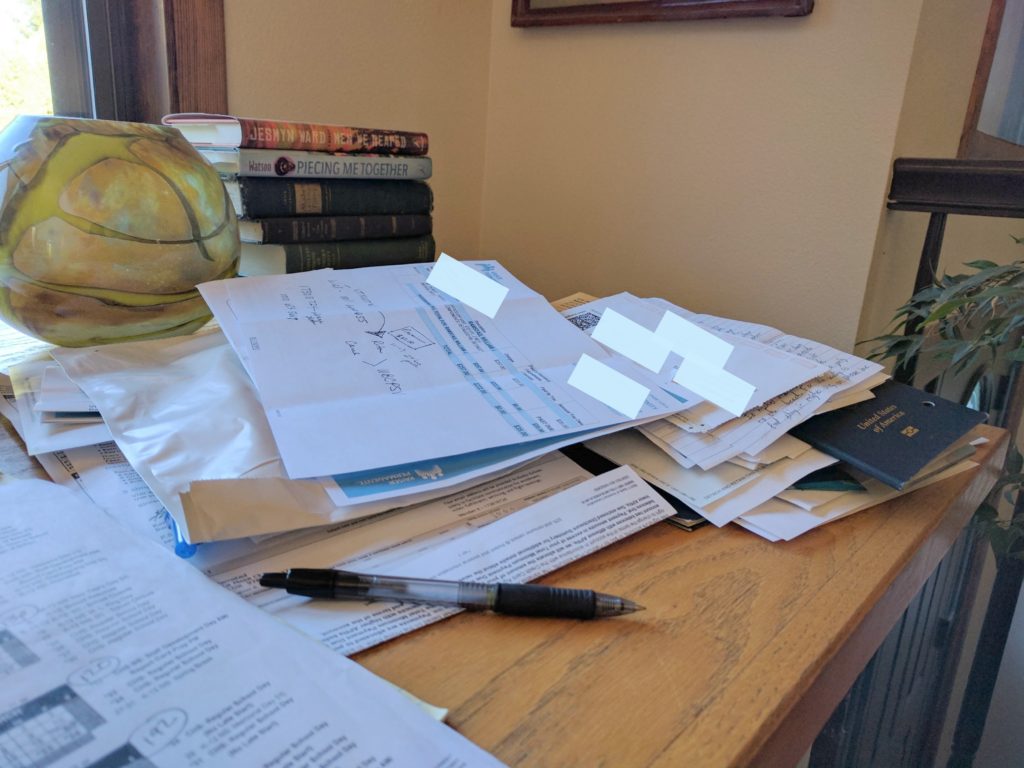

So, if I know I can’t read all the books I check out, what is my library habit really about? I’m not sure, but it’s a real thing, my librarioholism. It means I visit regularly, always leaving with a large haul that I fully intend to read, even as I know that I will not have (make?) enough time to read it all. Oh, I suppose I could, if I just wouldn’t let myself return for more until the books I already have are finished. But after about a week away, I get twitchy to go back, and I’ve come to accept that I’m not going to stop doing what I’m doing.

Maybe I’m hooked on the endorphins I get from anticipating a book, more than on anything I get from reading the book itself. (If I were Dinky Hocker and she actually shot smack, looking for books would be my smack.) Maybe what I’m really hooked on is the fix of the new and all its possibilities, all the different versions of myself that they promise I might be–a graceful homemaker, a fiber artist, a serious writer, a person who understands what the hell is happening in the world, to the world–and, by extension, to myself and those I love. Many of the books I check out are more aspirational than anything else. They are books I want to want to read more than I want to actually read, and I rarely get past the first pages of them, if I even pick them up at all. But still, I take them home. They teach me something about what some part of me–maybe a part I’m not even conscious of yet–wants or needs.

Hmmm… maybe it’s even deeper than that, and my habit is really some sort of hedge against death, against potential or probable annihilation of various kinds. See? my stack of books say to me. There is still time to be all of the things you might be and to live in the kind of world you want to inhabit. There are still people writing books about how to put on a nice dinner party, so maybe that’s something that might still matter and that you can still learn how to do. I have long joked that if the apocalypse comes and the grid goes down, I will not join the hordes looting the grocery stores; no, I will be looting the library, a space I’ve long claimed as my church, a sacred place to go for answers and community and comfort. Although I’ve been tongue-in-cheeking the addiction metaphor, maybe my habit truly is not so different from the addict’s drug or the believer’s religion, just another way of coping with fear.

Ah, look at me. I’ve written myself into a bit of a corner, and a dark one at that. And it’s Sunday morning and I’ve promised myself that I will post here once a week, ready or not. What’s the way out? I don’t know, any more than I know how to neatly tie up this package of words, but I’m guessing that if an answer can be found, it’s probably at the library. Better figure out how to fit a trip there into my plan for the day.

******

This post was prompted by a book I’ve been loving, Susan Orlean’s The Library Book. When I read about it, I thought it might be a little boring. It isn’t.

If you, too, are a librarioholic, you might enjoy these reads about our happiest place on earth:

This article was everywhere a few weeks back–or maybe it just seemed that way to me because so many people sent it to me and/or so many library friends shared it.

But more important than that previous article is this take on it from one of my favorite librarians.

I would go visit these gorgeous libraries, glorious as any cathedral.

It would be the coolest meta thing if this picture book about librarian Pure Belpre had actually won a Pure Belpre Award in the recent ALA Youth Media Awards event, but it was an Honor Book which means it’s still cool. Just not as cool as it could have been.

And, currently on my Likely to Be Overdue List Because I’m Actually Reading Them:

The Inviting Life by Laura Calder (648). I want to live this kind of life. I’m getting there.

On the Bus with Rosa Parks by Rita Dove (811.5) Don’t read this because it’s Black History Month. Read it because it’s good poetry.

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport (303.4833)–This one was recommended by my friend Marian, and now I’m recommending it to you. More on this later.

Daily Rituals Women at Work by Mason Currey (704.042). These are short, fascinating reads about the daily habits of women across various creative fields and eras. The chapters are like Lay’s potato chips: Small, savory, and you can’t eat just one.

The Small Backs of Children by Lidia Yuknavitch (Fic). I avoided this when it was published. I’m ready for it now. I’ve only just started it, but…Wow.

Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t by Steven Pressfield (808.02). Many things about Pressfield annoy me. I’m reading this book because Anne Lamott can’t be my only writing teacher. We should rub up against what annoys us from time to time.

The Things that Matter by Nate Berkus (747.092) Not your typical interiors-porn coffee table book. Though it is a coffee table book with gorgeous interiors. I’m reading it for the stories, not the pictures. Really! OK, for both I guess.